5 years in the past, the World Well being Group declared that the outbreak of a novel coronavirus, COVID-19, was a pandemic – a designation that in some ways marked the start of a brand new period in politics, public well being, media, and our on a regular basis lives.

The Monitor’s correspondents have coated all facets of this transformation, from the ache of households separated, to divisive college board protests, to the invention of quirky pleasure in new pastimes as an outlet. On this anniversary, they share a few of the shifts they’ve seen and the way the pandemic continues to affect international societies at the moment.

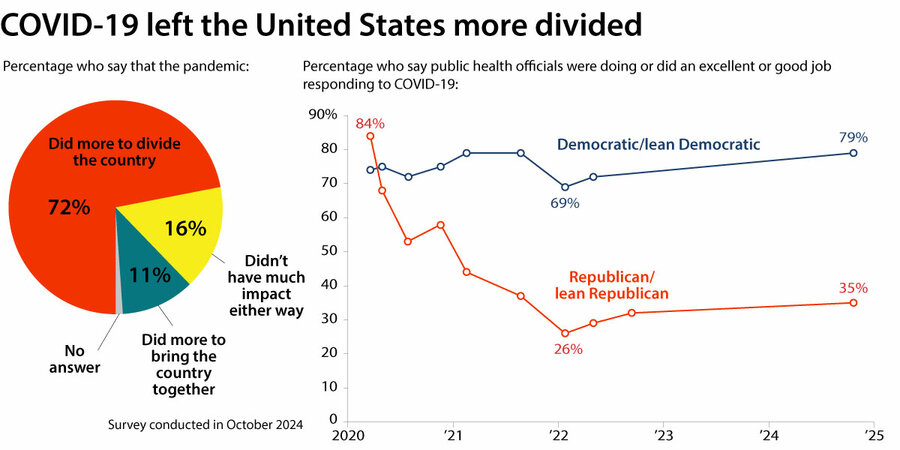

The pandemic took an immense human toll over the previous half-decade. In response to the WHO, greater than 7 million folks died due to the virus between 2020 and 2024, and the Facilities for Illness Management and Prevention nonetheless attributes hundreds of deaths each month to COVID-19. The financial toll of the pandemic and the rules round it proceed to gas a distrust not simply of the federal government, but in addition of these with totally different views in regards to the virus, drugs, and well being coverage.

Why We Wrote This

It was foremost a public well being disaster. However 10 of our reporters observe wider lasting results – from the office and politics to spiritual life and belief in elites.

Not every part was detrimental. Pivots prompted by social distancing necessities ushered in new alternatives and cultural phenomena. Six years in the past, “Zoom” was not one other phrase for conferences or a strategy to see household on-line.

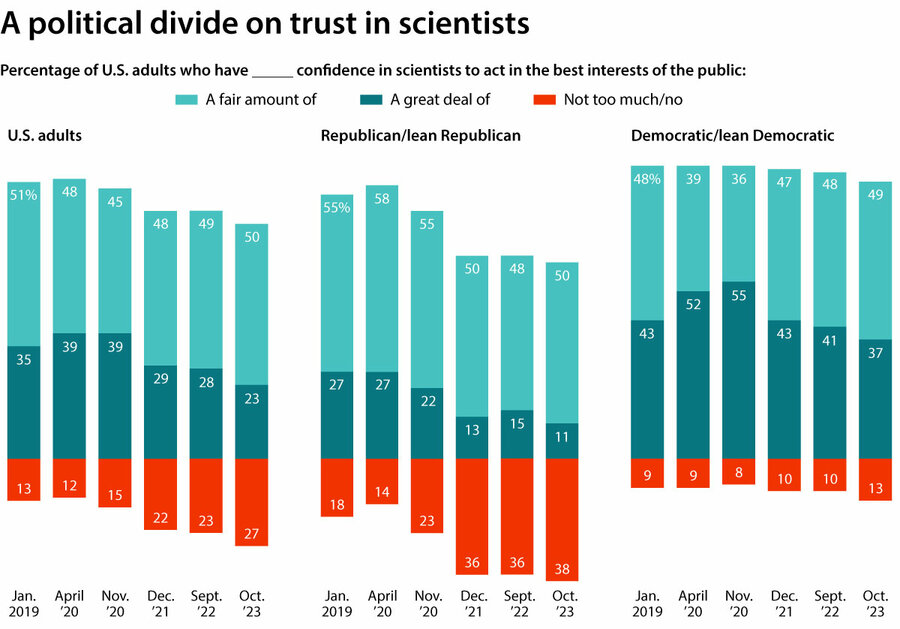

Nonetheless, in keeping with a latest survey from the Pew Analysis Middle, practically three-quarters of adults in the USA say the pandemic did extra to drive the nation aside than to convey it collectively. It highlighted, and exacerbated, variations in values across the rights of the person versus the rights of the group. Globally, polling as of 2022 confirmed an analogous pattern of countries feeling extra sundered than united.

Many consultants level out that the pandemic didn’t trigger this fraying. COVID-19 arrived at a second when mistrust and division had been already rising, and as a brand new media atmosphere was exacerbating these divides.

“While you put a pandemic right into a extremely unstable and divisive political context, we all know it’s going to be extremely tough,” says Allan Brandt, a historian of drugs and professor of the historical past of science at Harvard College. “Repairing and understanding what simply occurred to the world over the previous 5 years goes to be an necessary a part of our future.”

Now we have dispatches from 10 Monitor writers from around the globe to share with you.

“Science is actual.” It’s additionally sophisticated, and so is our relation to it.

Some months into the COVID-19 pandemic, I moved to a progressive city in western Massachusetts the place folks preferred to declare that they “believed in science.” That they had the rainbow “Science is actual” garden indicators to show it.

My out-of-school kids would ask me why so many science-lovers had been giving us soiled appears from their vehicles as we went for maskless runs on empty streets. I’d simply shrug.

Science is sophisticated, I’d inform them. That’s what makes it superb.

However I knew one thing profound was occurring – as did most of the scientists and public well being thinkers I’ve interviewed over the previous a number of years.

Because the U.S. swirled into competing narratives of what, precisely, COVID-19 was, and the way to answer it, “science” often turned a cudgel. Solely individuals who didn’t consider in science itself, the rhetoric on one facet went, would doubt the latest pointers from the Facilities for Illness Management and Prevention, the official clarification for COVID-19’s origins, the necessity to implement curfews. (All of these “information,” in fact, shifted throughout the pandemic.)

In the meantime, a brand new media panorama fueled an outrage that turned scientists and public well being officers into villains. That is a part of what Syracuse College Professor Amy Fairchild describes as a “backlash motion” that has essentially reshaped our political and cultural panorama.

Lacking from each stances was the acknowledgment that science is just not itself a factor or a reality, however an attractive, curiosity-driven course of wherein imperfect human data is all the time altering.

“Science is all the time evolving. It’s all the time contested. There are all the time gaps. There have been terrific scientific debates round, I don’t know, salt,” says Dr. Fairchild. “Science is all the time working in a context the place social values and priorities are at play.”

However the media and political forces underlying this pandemic made it significantly tough for these working in science to stay in that nuance – and it pushed many to declare certainties that finally undermined belief, consultants say.

– Stephanie Hanes, atmosphere and local weather author

In Michigan and past, an altered politics

For a lot of Michigan voters, the backyard facilities had been the ultimate straw.

When states first started issuing stay-at-home orders 5 years in the past in March 2020, as they grappled with the specter of a brand-new virus, People had been largely supportive. In Michigan, Democratic Gov. Gretchen Whitmer’s preliminary orders to shut colleges and companies had widespread approval – even amongst Republicans.

However as shutdowns had been prolonged and expanded, voters’ persistence and confidence of their political and public well being leaders started to waver. When Ms. Whitmer issued an government order that April closing backyard facilities and plant nurseries, the pushback was so robust she was quickly pressured to rescind it.

A 12 months and a half later, after I was on a reporting journey in Michigan, voters from each events nonetheless introduced up the closed backyard facilities. And whereas the anger from Republicans was extra visceral, many Democrats additionally informed me, in decrease voices, that they believed that exact order had gone too far. Ms. Whitmer handily received reelection in 2022, thanks partly to the Supreme Court docket’s overturning of Roe v. Wade that very same 12 months, which helped enhance Democratic turnout for a number of contested governorships.

Politically, probably the most lasting legacy of the pandemic will be the means it decimated belief in authorities. To make certain, the extent of belief was already low – after hitting a quick excessive level following the 9/11 terrorist assaults, belief in authorities has stayed beneath 30% ever since late 2006, in keeping with the Pew Analysis Middle. However after the pandemic, officeholders from the state to federal stage noticed their approval rankings collapse, whereas anti-government sentiment rose total, significantly amongst Republicans.

The backyard facilities in Michigan had been a window into why. Many citizens mentioned Governor Whitmer’s order, which restricted an outside exercise – gardening – appeared irrational and extreme, even on the time. It made them query the selections of these in energy and the proof supporting different restrictions.

In hindsight, in fact, it turned clear that plenty of measures, like college closures, seemingly did extra hurt than good. Even amongst those that nonetheless consider officers did one of the best they might with restricted data, the affect on belief in authorities appears more likely to linger for a while.

– Story Hinckley, nationwide political author

Sweden reveals an alternate response

Whereas a lot of the world was studying to grapple with a brand new and scary problem, Sweden watched the pandemic unfold as if it had been a film. Eerie streets in New York and overwhelmed hospitals in Milan got here as heart-wrenching scenes. However that was occurring on the market. In Sweden, cafés remained crowded. Kids went to highschool. Many individuals didn’t put on masks.

There have been some pointers for distancing in public, and we had been suggested to remain dwelling when sick and to restrict gatherings. But it surely was largely left to the person to determine what that meant.

On the time it was seen as an irresponsible gamble. Later it was known as a hit story. There weren’t extra deaths in Sweden than in neighboring international locations, regardless of a spike at first. College students didn’t lose years of studying.

Some say Sweden lived by way of the pandemic in denial. Which may be, whereas these in nursing houses confronted the brunt of pandemic-attributed deaths. However the experiment might also have proven what Sweden intuited from the beginning. Individuals wish to be trusted as people. If that freedom is used responsibly, it builds extra belief. Opposite to what occurred in most locations, Swedes reported feeling extra united than they did earlier than the pandemic.

Sure, Sweden continues to really feel stiff and uninviting to these not already within the fold. However someplace inside its staunch individualism, Sweden managed to search out an uncommon togetherness that weathered a pandemic.

– Erika Web page, international economic system author

A tricky hit to training – and glimpsing paths to restoration

Early in 2022, teams of younger college students gathered within the college cafeteria in Elizabethton, Tennessee, to sound out phrases like “ball.” Tutors patiently helped every youngster mix the letter sounds collectively.

On the time, I used to be at this elementary college within the Appalachian Mountains masking Tennessee’s new tutoring corps. The state was utilizing pandemic reduction funding to spend money on “high-dosage, low-ratio” tutoring. It’s one of many approaches that researchers say can finest assist college students who’re behind, as many nonetheless are, lengthy after the pandemic’s disruptions.

The college’s principal supplied a prescient warning. He nervous the state wouldn’t lengthen the corps as soon as federal funding ran out. That occurred final summer time.

“Issues that we all know work, like tutoring, utilizing confirmed curriculum and educational methods, particularly for literacy and math, these actually nonetheless are lagging,” says Robin Lake, director of the Middle on Reinventing Public Schooling.

The educational loss children skilled, and the way it hit college students in lower-income colleges hardest, is likely one of the thorniest legacies of the pandemic. Schooling reformers are calling for extra innovation, like bringing in-school tutoring again. Households wish to different fashions: Homeschooling, whereas previous its pandemic peak, accounts for 4% of the school-age inhabitants, up a proportion level since 2016. Constitution college enrollment is up practically 12%.

Because the long-term restoration continues, the college within the Tennessee mountains presents a lesson. College students and academics discover pleasure in mastering the ABCs, however it takes persistence.

– Chelsea Sheasley, nationwide information workers editor and former training author

In China, an financial hit from striving for “zero-COVID”

Every time I bicycled to the tiny tea store off a residential alley in Beijing, the talkative proprietor informed me a bit extra of her story.

Hailing from the tea-rich Fujian province in southeastern China, she’d moved to Beijing together with her husband and younger son a number of years earlier to launch her store. Enterprise was brisk, she mentioned, till a few of the strictest pandemic lockdowns struck Beijing laborious in early 2022. “Now, it’s horrible,” she complained in her rapid-fire Fujianese accent, surrounded by cabinets stuffed with tea however no consumers.

Touring round China, I’ve requested scores of small entrepreneurs how their companies are faring. More often than not, they are saying, “It’s no good.” Months of necessary closures ate away their financial savings – and too few prospects have up to now returned.

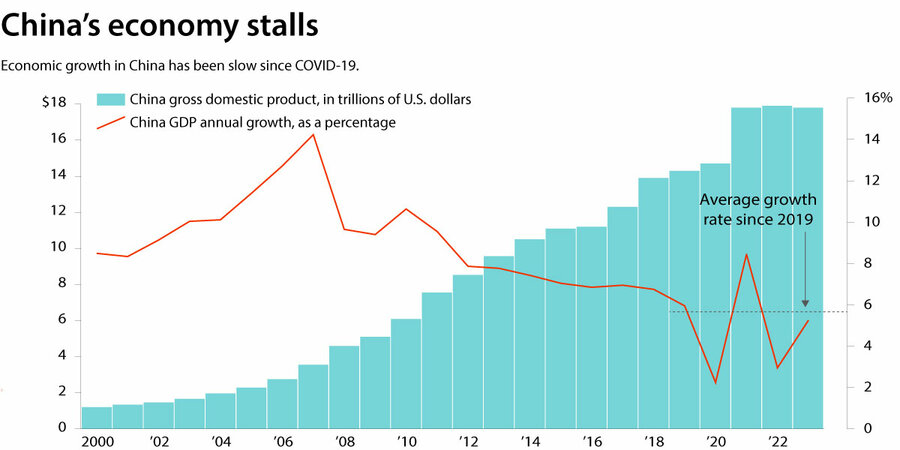

I typically thought in regards to the prices of Chinese language chief Xi Jinping’s insistence that authorities try for zero COVID-19 instances. This top-down coverage required huge testing and quarantining of the inhabitants, coupled with sealing off huge cities and shuttering most companies every time tiny outbreaks occurred. The coverage proved untenable and was lifted in December 2022, however China’s economic system continues to be struggling to get well.

The Chinese language are adjusting to this new regular. A younger graduate scholar in central China, laborious put to discover a job, mentioned she’s pursuing a extra laid-back way of life.

In Beijing, I pedaled to the tea store to search out that the hard-working proprietor had taken on a brand new gig to attempt to make ends meet. She’d turned her store right into a distribution level to assist neighbors save on supply fees – capturing a small return for herself.

“Sorry, I’ll be with you in only a minute!” she informed me, as she sorted a grocery order. “No drawback!” I mentioned, smiling. My tea may wait.

– Ann Scott Tyson, Beijing bureau chief

Pandemic response spurs youth activism in Africa

Once I moved to South Africa from the U.S. a decade in the past, on the age of 25, many individuals in my life puzzled why. By then, the nation’s glittering second as Nelson Mandela’s rainbow nation appeared firmly up to now. As an alternative, it was within the unsure throes of adolescence, beset by corruption scandals and political infighting.

However I used to be struck how impermanent these troubles felt to many South Africans my age. Within the U.S., I had been raised to consider that concepts and establishments modified slowly. Younger South Africans, alternatively, lived in a society that had reworked radically lower than a technology earlier than. For them, the nation’s future was moist clay, practically completely malleable, they usually had been desperate to get their palms soiled. As I traveled Africa, the world’s youngest continent, I noticed this type of hope and willpower in every single place.

Over the previous few years, I’ve watched because the pandemic and its aftermath cranked up the quantity on the ambition of younger Africans to construct societies extra simply and democratic than these of their mother and father and grandparents. From Nigeria to Senegal to Kenya, younger folks have poured into the streets. They had been protesting leaders they are saying failed them throughout the pandemic, whether or not within the type of proscribing private and political freedoms within the title of illness management, or failing to defend their populations from a tanking international economic system.

Even when these protests have been brutally suppressed, as in Mozambique, the place lots of of younger folks died protesting a extremely disputed election final 12 months, their calls for stay pressing. One younger lady there, Estância Nhaca, informed my colleague Samuel Comé one thing that echoes throughout the continent.

“It’s not over but.”

– Ryan Lenora Brown, Africa editor

Returning to locations of worship

The pandemic’s impact on religion providers was drastic. Homes of religion stopped holding in-person providers in a single day. Congregants discovered themselves worshipping alone at dwelling over Zoom, somewhat than sitting shoulder to shoulder with their group. Some homes of worship sued states, arguing that closure orders aimed toward public well being had been harming spiritual freedom. Religion leaders nervous congregations wouldn’t return, that the pandemic would possibly spell a precipitous drop in an American spiritual life that was already changing into extra secular.

Their worries weren’t unfounded. Over the previous a number of many years, researchers had tracked a gradual sample of spiritual decline. However a shock emerged from the pandemic: Over the previous 5 years, the variety of spiritual People has stabilized.

About 24% of U.S. adults mentioned their religion grew stronger on account of the pandemic, in keeping with a survey by the Pew Analysis Middle in 2020. Solely about 2% mentioned their religion turned weaker. In Pew’s latest survey on faith, concluded final 12 months, some 83% mentioned they consider in God or a common spirit.

“Cognitively, this sense of religion getting stronger or deeper or extra mature from the pandemic could have contributed to the steadiness we’ve seen up to now few years, possibly not inflicting spiritual development total, however at the very least halting the sample of decline,” says Chip Rotolo, a faith and public life analysis affiliate at Pew.

Communities usually pull collectively within the face of catastrophe – although a worldwide pandemic is many levels bigger than different examples, says Dr. Rotolo. After the Sept. 11 assaults in 2001, Pew information confirmed unity amongst spiritual communities throughout the U.S.

As we speak, most individuals who would usually attend religion providers in particular person are again to doing so. “There is usually a sense, when occasions like this occur, that individuals need to search significant group like they could discover of their spiritual communities, or begin being extra engaged,” he says.

– Sophie Hills, faith author

On campus and past, a harsher edge to politics

The pandemic acted as a catalyst for political radicalization. Social isolation and rampant on-line misinformation mixed to push many individuals into extra excessive political positions – and in some instances, actions.

On my faculty campus, I noticed college students abruptly itching to have an outlet for his or her frustrations. After the homicide of George Floyd in Might 2020, Black Lives Matter protests erupted throughout the U.S. Whereas the bulk had been peaceable, some resulted in looting and arson as protesters descended on abandoned downtowns. The Jan. 6, 2021, riot on the U.S. Capitol was a stunning outburst of political violence, as Trump supporters tried to disrupt the peaceable transition of energy.

A March 2021 survey discovered 15% of People agreed that “As a result of issues have gotten up to now off observe, true American patriots could should resort to violence with the intention to save our nation.” That quantity rose to 23% in September 2023, however dipped again right down to 18% this previous fall.

Extra not too long ago, we’ve seen the once-unthinkable glorification on social media of Luigi Mangione, the person accused of murdering UnitedHealthCare CEO Brian Thompson. And there’s been a rise in threats towards politicians. In 2018, the Capitol Police investigated 5,206 threats towards members of Congress; in 2021, it investigated 9,625. The quantity has been above 8,000 ever since.

– Nate Iglehart, workers author

Mexico’s casual employees persist – with out safety nets

For a lot of casual employees, like Obdulia Montealegre Guzmán, who sells corn-based treats like huaraches at out of doors markets in Mexico Metropolis, making it by way of the pandemic together with her enterprise and household intact got here right down to ingenuity.

“We stayed dwelling for a month, however by no means actually stopped working,” says Ms. Montealegre. Her daughter helped create a advertising plan for her mother and father on social media. They now settle for to-go orders through WhatsApp, drastically upping day by day gross sales.

I’ve been in contact with Ms. Montealegre a number of occasions over the previous 5 years. She has all the time had an optimistic outlook, even when she was wrapping her enterprise in industrial-size plastic wrap as an early-days well being measure towards the unfold of COVID-19. However I used to be stunned to listen to that at the moment, she sees the pandemic squarely within the rearview mirror.

Challenges going through her and her neighbors – from rising inflation to a weakening peso – don’t have any by way of traces to the pandemic, she says. It’s extra a mirrored image of governments that for many years haven’t managed the economic system effectively. Virtually 60% of Mexican laborers are thought-about casual wage-earners who don’t have entry to social safety or employment advantages like paid go away.

There was no notable drop in belief in public officers in Mexico following the pandemic, partly as a result of that belief has traditionally been low in Mexico and within the area. Knowledge from Latinobarómetro, a regional polling agency, discovered that only one in 5 folks in Latin America expressed belief of their governments between 2009 and 2018, for instance.

“This sort of work is basically exhausting and means simply hustling on a regular basis,” says Ms. Montealegre. “However our challenges lengthy predated COVID.”

– Whitney Eulich, Latin America editor

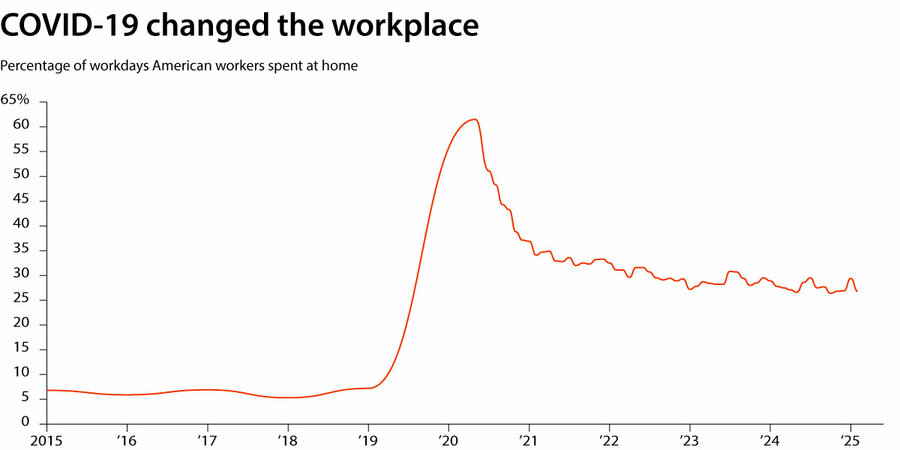

In a modified office, will in-person work make a comeback?

My first newsroom, which housed the coed newspaper I labored for in faculty, was dynamic. It was full of exercise as we whipped tales into form, argued over grammar, and gently coaxed one of the best out of one another. I assumed that skilled newsrooms would even be hotbeds of exercise the place you possibly can be taught by way of osmosis.

However the actuality was much less romantic. Once I began on the Monitor in 2023, the pandemic had emptied out places of work, newsrooms included. The spirited discussions that for me outlined journalism largely occurred on Zoom or Slack.

Because the youngest particular person on workers, I puzzled how this might have an effect on my profession. Some researchers say that if you’re simply beginning out, working in particular person is crucial for studying. One buddy, a software program engineer, as soon as texted me that he “can actively really feel [his] profession rising sooner” when he works face-to-face.

Now, at the same time as many employers intention for a better return to places of work, this problem is affecting not simply the information media however a bunch of industries.

It’s not that newsroom camaraderie is gone. I nonetheless really feel linked to my colleagues, even when edits occur over Zoom. But it’s laborious to think about that workplaces will ever be fairly the identical.

As we speak, as folks trickle again to the workplace, we’re getting a few of that outdated newsroom power again. And although how we come collectively has modified, one factor hasn’t: Journalism – or, actually, any work – can solely occur by way of collaboration.

– Cameron Pugh, workers author and editor

This text was reported by Stephanie Hanes in Northampton, Massachusetts; Story Hinckley in Richmond, Virginia, Erika Web page in Madrid (with pandemic visits to Sweden); Chelsea Sheasley in Boston; Ann Scott Tyson in Seattle and Beijing; Ryan Lenora Brown in Johannesburg; Sophie Hills in Washington; Nate Iglehart in Boston; Whitney Eulich in Mexico Metropolis; and Cameron Pugh in Boston.